When In Rome - A Guide to Traditional Fasting

Source: https://onepeterfive.com/

From the first pages of Scripture, God teaches us the spiritual power of abstaining from food. Adam and Eve’s first command was a fast—not to eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Their sin came from eating what God forbade. Even in humanity’s earliest days, food was a test of fidelity.

Before the Flood, man did not eat flesh; Noah was the first to receive permission to eat meat, and from that moment forward, the Church has understood food not merely as nourishment, but as a realm of spiritual discipline.

Why Fast?

The traditional Catholic answer is both simple and profound:

1. To bridle the lusts of the flesh

Our bodies, weakened by original sin, often lead us into sin. Fasting disciplines the senses and strengthens the will. It is a small “violence” done to our appetites for the sake of holiness. Christ Himself said that “the kingdom of heaven suffers violence” (Matthew 11:12) —the saints understood this as the violence we do to ourselves, the self-denial that allows virtue to grow; that entering the kingdom of heaven requires a strong, committed effort.

2. To free the soul for contemplation

When we fast, we cook less, prepare less, indulge less—and this gives more time for prayer. The Fathers often said that fasting makes the mind clear and lifts the heart upward. St. Basil taught that our guardian angels draw nearer to us depending on how cleansed our souls are through fasting.

3. To make reparation for sin

Penance is required of every Christian. If Christ Himself—sinless, spotless—did penance, why would we ever think we are absolved from it? When we fast, we willingly accept hardship to atone for our own sins and the sins of the world.

And yet the Church, understanding human frailty, has always allowed alternative penances when fasting cannot be done: almsgiving, extra prayer, or acts of mercy. But the principle remains: penance is not optional.

Traditional Catholic Fasting: What It Used to Be

Modern Catholics would scarcely recognize the fasting of our forefathers. For most of Church history, traditional fasting meant:

No meat or wine

Remember: Noah was the first to eat meat and to drink wine; to refrain from these things is a return to Edenic simplicity.No animal products of any kind

Eggs, cheese, milk, butter—none of these were permitted. Fasting meals were essentially vegan.Fish was not allowed until the 9th century.

Water was traditionally not consumed until after sunset.

In honor of Christ’s thirst on the Cross, no beverages at all were taken between noon and 3 PM on Good Friday.Fasting lasted until sunset.

A single meal was eaten in mid-afternoon, with later concessions adding:

a small morning snack (frustulum, literally “a piece”)

an evening snack (collation)

Abstinence even on Sundays in Lent.

Lent was a marathon, not a sprint to Sunday indulgence.

The Lenten Fast

Traditionally, from Monday through Saturday of Lent:

One meal at 3 PM

A small collation in the evening

No animal products

No food on Ash Wednesday or Good Friday

Holy Week involved an even stricter fast, consisting only of bread, water, salt, and herbs.

The Church assumed all the faithful would do “hard things”—and believed deeply that hard things are worth doing.

Advent: The Forgotten Fast

Advent once mirrored Lent. Beginning in 480 in Tours, Christians fasted on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays—known as St. Martin’s Lent.

Fun Fact: The phrase “When in Rome, do as the Romans do”, stated by St. Ambrose of Milan, refers to the practice of adopting Roman customs when in Rome, even by non-Roman Catholics, who would fast according to how the Roman Catholics did.

Feasting Requires Fasting

The Church has always seen feasting and fasting as two sides of the same coin. You cannot have the joy of Easter without first embracing the hunger of Lent. This is why…

Brazil’s Carnival Festival (“carne, vale!” — “farewell to meat!”) developed as a last celebration before strict fasting.

Easter eggs became a symbol of celebration because eggs were forbidden during all of Lent.

How We Lost the Fast

Over centuries, a mountain of dispensations hollowed out the once-rigorous discipline:

Local regions had different rules.

Colonies inherited the rules of their mother countries.

Crusade Bulls (La Bulla de la Cruzada) gave Spain and its colonies exemptions as a reward for driving out Islam.

The Baltimore Councils of the 1800s finally simplified everything by adopting the lowest common denominator, just to restore uniformity.

And the great turning point—the “Pearl Harbor of fasting”—came on May 31st, 1731, when Pope Benedict XIV allowed meat to be eaten during Lent. From there, the tradition steadily softened.

Eventually, Friday fasting became mere Friday abstinence.

Exemptions (Traditional)

Certain persons have always been excused from fasting (but not from abstinence):

Pregnant women

Nursing mothers

Manual laborers

The seriously ill

The elderly (60+)

Young children (under 9)

Allergies, preferences, or “just not feeling like it” were not exemptions.

Wednesday and Saturday: Traditional Weekly Fasts

The early Church fasted on Wednesdays and Saturdays:

Wednesday: the day of Christ’s betrayal

Saturday: the day Christ lay in the tomb

These ancient fasts once shaped Christian life as much as Sunday Mass.

Our Lord Fasted—Therefore We Must Fast

Christ did not command a 40-day fast before Easter. But He did fast for 40 days—because He was following the Old Testament fast. If the Son of God Himself entered the desert, who are we to claim exemption?

The saints urge us not simply to endure fasting but to come to love it.

To see in it a weapon against sin.

A cleansing for the soul.

A preparation for heaven.

Returning to the Ancient Discipline

We live in an age that flees from anything difficult. The Protestant Reformers encouraged Christians to step away from demanding practices. Modern culture tells us comfort is a right.

But the tradition of the Church tells us something very different:

Hard things are worth doing.

Fasting humbles the body, strengthens the soul, repairs sin, prepares the heart for prayer, and unites us with the suffering Christ.

Our Lord fasted.

Our ancestors fasted.

The saints fasted.

Let us, in our own small ways, begin again and “do as the Romans do”.

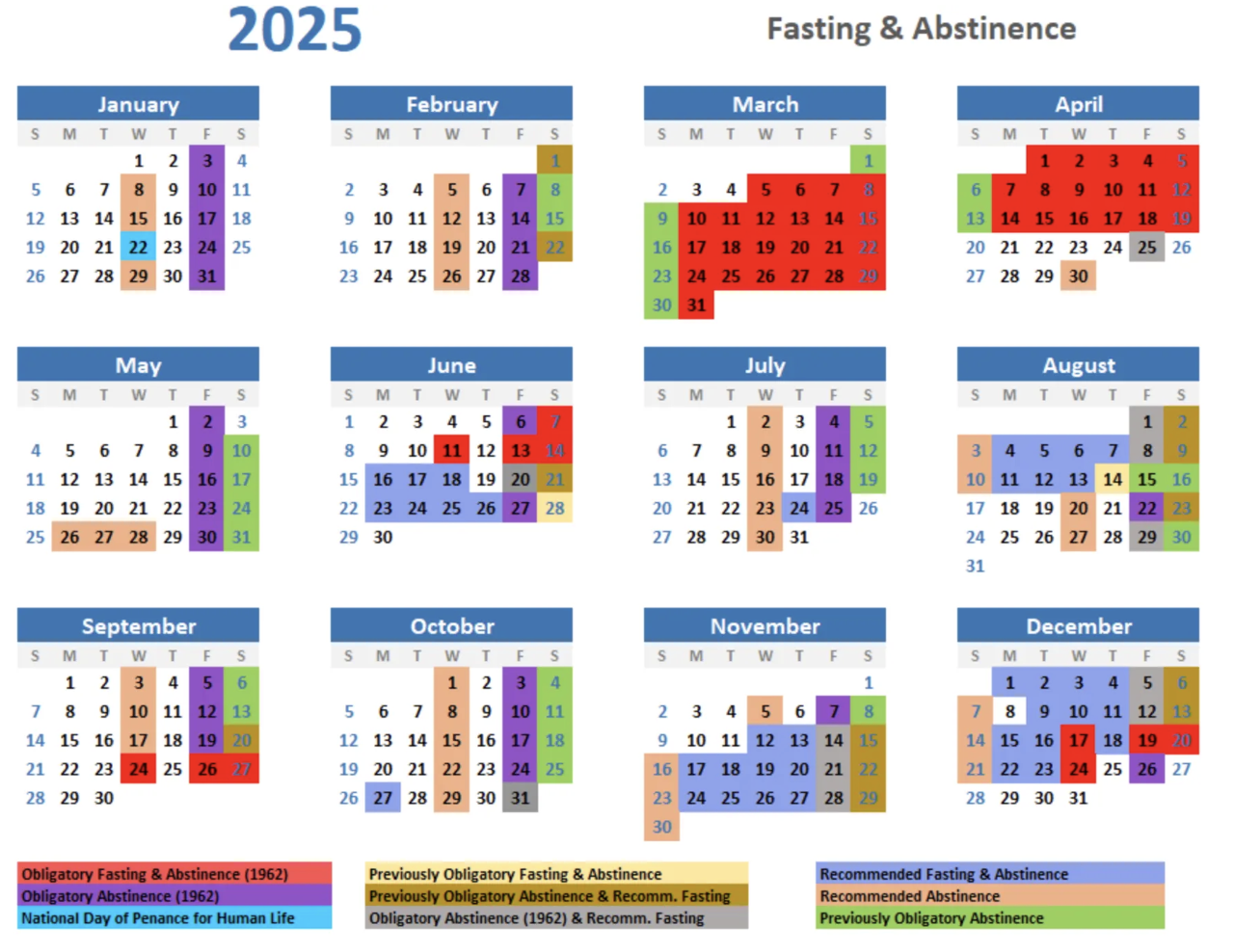

Learn More: The Definitive Guide to Catholic Fasting & Abstinence by Matthew Plese